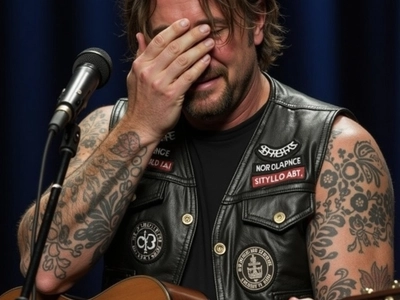

My name is Johnny. I’m forty-five, and the most important thing in my life has always been my daughter, Stephanie. That’s not just a nice line I tell people. It’s the truth I wake up to every morning and the reason I push through every hard day. For ten years, since her mom passed away, I’ve been dad, mom, chauffeur, homework checker, chef, late-night talker, and the person who holds the umbrella when everything else feels like a storm. We have our routines and our jokes and our quiet, ordinary little world. It’s not fancy. It’s ours.

When Stephanie was seven, I gave her the big room at the end of the hall with the private bathroom. People told me I was spoiling her. Maybe I was. Or maybe I just wanted her to have a corner of the house that felt safe and steady after life had shaken us so hard. We painted the walls a soft sea-green because it was the color of a scarf her mom used to wear. The window looks over the old maple in the yard. The closet still smells faintly of the lavender sachets her mom loved. There’s a shelf with framed photos: Stephanie missing her front teeth, her mom holding a sparkler on the Fourth of July, the three of us squinting into the sun at the beach. Her art supplies live in a rolling cart by the desk. There’s a little jewelry box—her mom’s—that plays a tinny song when it’s opened. It sticks sometimes. You have to jiggle the lid. Steph knows how to do it, and every time she does, she smiles like she’s visiting with a memory.

So, yes, the room is big, and yes, it has a bathroom, and yes, there are memories everywhere. That’s the point. It’s the one place in the world where I can’t fix everything but I can make sure she feels close to her mom, and, by extension, close to me. That room has seen late-night tears and early-morning laughter. It’s watched her go from little-kid pajamas to band T-shirts, from picture books to heavy textbooks, from bright finger paints to careful graphite shading. It’s not just a room. It’s a timeline.

When I met Ella, I had been single for a long time. She was funny and warm, and she said she understood that Stephanie came first. She had four kids from her previous marriage. That was a lot, and I knew it. But we took things slowly at first. We had dinner together. We went to the park. We did movie nights with pizza on paper plates. There were good days when it felt easy, like we were all part of some larger laughter. There were also hard days when it felt like we were trying to push two different puzzles together and force the pieces to fit.

By the time we’d been together three years, I’d seen the mix of it all. I’d seen her discipline style, which ran a little sharper than mine, and I’d seen how my patience sometimes frustrated her. I’d seen the way Stephanie looked at me for reassurance when there were new rules, and I’d seen the way Ella’s kids looked at me, testing whether I was someone they could trust or someone they had to outlast. Family isn’t just blood; it’s also habit and rhythm. Ours were still learning how to meet.

Then Ella’s lease ended earlier than she expected. The landlord decided to sell the place, and she had to move. She asked if she and her kids could move in with us. It wasn’t a small ask, but life rarely gives neat, easy questions. I took a breath and tried to picture all of us in the house. I thought about the hallway, the kitchen, the laundry, the sound of six alarms going off on school mornings, the constant hunt for missing socks. I tried to imagine how the air would feel, where the noise would go. Then I looked at Stephanie.

She didn’t say anything. She almost never complains. She’s a quiet, steady kid. But her eyes flicked toward her room, and then back to mine. That was the only signal I needed. I told Ella yes, they could move in, but there was one thing I wouldn’t bend on: Stephanie keeps her room. The big room stays hers. The private bathroom stays hers. Her shelves and her desk and her photos and her mother’s quilt stay right where they are. It wasn’t a negotiation point. It was the condition.

Ella didn’t like it. She didn’t yell, but her mouth tightened, and she used that careful, light tone people use when they’re trying to sell you on something you’ve already said no to.

“It isn’t really fair, Johnny,” she said. “I mean, my girls have shared rooms their whole lives. There are two of them, and they’re growing fast. That room would be perfect for them, with the bathroom and everything. Steph could take one of the smaller rooms. She’s just one person.”

“She’s not just one person,” I said, feeling a tired anger start to climb my spine. “She’s my daughter. And that room is full of her mom. It’s full of things we don’t move. I’m not changing my mind about this.”

Ella shrugged, then used a word that made my skin crawl. “It’s like a shrine. I’m just saying—”

“It’s not a shrine,” I said. “It’s a bedroom. A teenage girl’s bedroom. She draws in there. She reads in there. She FaceTimes her friends in there. She sleeps in there and dreams in there. And it’s staying her bedroom.”

She let it go, or said she would. She put her hand on my arm and told me she understood. She repeated it in front of Stephanie, and I remember thinking, good, we’re clear.

The night they moved in was chaotic, like all moves are. Boxes showed up labeled in a dozen different ways, some right, some not. There were half-taped lids and a box of kitchen spoons that somehow had a hairbrush in it. We brought in bags of clothes, a desk lamp, a wobbly tower of board games, and a stack of framed art of sunflowers and inspirational quotes. The younger kids ran in and out, asking where to put things. My dog hid behind the couch like it was a thunderstorm. I tried to keep my tone calm and give everyone a task. “Shoes by the hallway closet. Dishes in the sink for now. We’ll wash them and sort them tomorrow. If you find a towel, put it in the bathroom. Any bathroom. We’ll figure it out.”

The house had a new sound that night. Bigger. Busier. I felt it. Stephanie felt it too. She hovered near me, a little too bright, making big smiles for the younger ones, saying “Welcome,” and “Here, I can help,” and “Do you want water?” She’s fourteen but sometimes seems old, like she’s seen more than kids should have to see and learned how to make polite space for other people’s mess. I hugged her shoulder when I passed her. “We’ve got this,” I said in a low voice, and she nodded.

By ten, we were all wrung out. Ella said she would get the kids settled and I should get some sleep. I told her I had an early shift and would be out the door by six. “I’ll help with more unpacking after work,” I promised. “We’ll get it organized.”

She kissed my cheek and told me not to worry. Everyone was tired. Everyone wanted it to go smoothly. I took another walk down the hall before bed and glanced into Steph’s room. Her lamp was on. The quilt—her mom’s quilt—was folded at the end of her bed, the way she likes it. Her art cart was parked by the desk, pens and pencils in their jars. Her jewelry box sat on the dresser, lid closed. She gave me a small smile, and I gave one back. We were okay.

The morning came too fast. I left while the house was still dark. On the drive to work, I thought about breakfast and school schedules and how we’d draw up a chore chart so nobody felt like they were getting a raw deal. I thought about how to make this big change feel fair and safe. I told myself that love is work, and I wasn’t afraid of work.

The day ran long. I texted Stephanie at lunch: “How’s it going?” She sent me a thumbs-up and a sleepy face. “Still tired,” she wrote. “I’ll nap after school.” I sent a heart. I texted Ella, too. “Need anything?” She replied with a smiley face and said, “All good. Girls are excited.”

When I got home near dusk, the house was quiet in that heavy way that makes you whisper. I put down my keys and scanned the room for clues about how the day had gone. There were shoes by the door and a half-empty cup on the table. I noticed a light on in the basement stairwell, which was unusual. I didn’t think much of it yet. Then I turned and saw Stephanie on the couch. She was curled into herself, knees drawn up, sleeves pulled down over her hands. When she lifted her head, her eyes were red and swollen.

“What happened?” I asked, already feeling the heat rise under my collar.

“She moved me, Dad,” she said, voice small and rough like it had been sandpapered. “My stuff’s in the basement.”

I stared at her. For a second, my brain just refused the words, like when you try to plug a cord into the wrong socket. “What do you mean, she moved you?”

“She moved me,” Stephanie repeated. She enunciated each word like she was afraid she’d lose control if she didn’t. “I came home and my room—my room—was full of their stuff. My clothes were on the floor. The quilt was off my bed. My art cart was gone. She said the basement would be ‘cozy’ and I should be ‘flexible.’”

I didn’t say anything. I walked to the basement door and opened it. The light was on. The air was cooler down there, and it smelled like detergent and old wood. At the bottom of the stairs, I saw it: a rough pile of Stephanie’s life. The art supplies were tipped sideways, pens and pencils spilling like a broken rainbow. A stack of her notebooks lay half-open, pages bent. One of her framed pictures of her mom had slid against a box and was facing the wall. And there, on the cement floor next to a laundry basket, sat the little jewelry box, its lid knocked crooked. I could hear the music inside, that tinny song, trying to play through the resistance. It made a brave, warped sound that hurt me in a way I didn’t have words for.

I went up the stairs two at a time. My voice was already gone tight in my throat, so what came out wasn’t calm or measured. “Ella!”

No answer.

I walked down the hall toward Stephanie’s room. The door was open. The sea-green walls were there, but now the bed had different pillows on it. There were two backpacks on the floor, with keychains I didn’t recognize. The closet door was open and new clothes hung there, bright and messy. And on the bed, two of Ella’s girls were sitting cross-legged, wearing Stephanie’s shirts like they were trying on costumes. One of them bounced a little, making the mattress squeak. Between them, spread out and smeared with the sound of new hands, was Stephanie’s mom’s quilt.

My hands shook. I couldn’t decide whether to pick up the quilt and fold it or to pull the shirts off the girls’ shoulders or to explode into a thousand pieces and let the house sweep me up. I did none of those things. I turned away and went into the kitchen. Ella was leaning on the counter, scrolling on her phone like she was waiting for a ride.

“We need to talk,” I said.

She looked up, eyebrows raised like I was a sales clerk with a return policy she didn’t like. “About what?”

“You moved my daughter,” I said. “You moved her out of her room. You put her stuff in the basement. You let your girls wear her clothes and sit on her mother’s quilt.”

Ella’s lips pressed together for a second, then she put the phone down with a sigh. “I thought you might react like this,” she said, “but Johnny, we have to be reasonable. Two girls need more space than one. It’s only fair they get the bigger room and the bathroom. Stephanie is a teenager. She can handle change.”

“No,” I said. “No, she shouldn’t have to handle this kind of change. We talked about it. I made it clear: Stephanie keeps her room.”

Ella shrugged a little. “I tried to talk to her about it, but she got emotional and said it was about her mom and memories. I’m sorry, but your daughter needs to learn she’s not the center of the universe. We are a family now. Everyone shares. Everyone compromises.”

I stared at her, stunned by the way she could make cruelty sound like balance. “Compromise isn’t stealing someone’s space while they’re at school,” I said. “Compromise isn’t throwing her things in a heap. Compromise isn’t letting your kids wear her clothes. And compromise sure as hell isn’t spreading your kids out on her mother’s quilt like it’s a picnic blanket.”

“They’re kids,” she said, as if that excused everything. “They’re excited. You’re being dramatic.”

Something went still in me then. There are moments in life when you can feel the floor tilt and you know it’ll never tilt back. I looked at Ella—at her smooth, irritated expression, at the way she spoke about fairness while standing on my child’s heart—and it was like looking at a lock that would never open. I saw that this would be our life if I let it: endless arguments about what was “fair,” where “fair” meant everybody except Stephanie, and “family” meant my daughter had to shrink so someone else could spread out. I thought about the ten years we’d spent surviving grief and building a home where the worst pain had a place to sit and breathe. I thought about how easily Ella had marched right in and put her hands all over it.

I took a breath. It was a big, quiet breath that came from a deep place. I said, in a voice I hardly recognized, “Give me your hand.”

She frowned. “What?”

“Your hand,” I repeated.

She held it out, cautious, and I took it. I slid off the engagement ring I had given her. It was simple, nothing flashy, a promise in a circle. I set it on the counter between us. It made a little sound, a tiny click like the end of a sentence.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I’m ending this,” I said. “I won’t marry someone who thinks my daughter’s home is a bargaining chip. I won’t live with someone who calls her grief a shrine and her room a privilege. You moved in last night. You’ll move out tonight. I’ll help you find a hotel. Tomorrow you can get your things. But you’re not staying here.”

For a second, she just stared at me, wide-eyed, shocked that the world had not bent her way. Then her mouth opened and out came a stream of blame and disbelief. I let it wash past me. I didn’t care what she called me. I cared about the girl on my couch with red eyes and sleeves pulled over her hands.

I turned away from Ella and walked to Stephanie. I sat beside her. She leaned into me before I even opened my arms, like she had been waiting to collapse. I held her and felt her breath hitch, hitch, hitch, and then slow. “I’m so sorry,” I said into her hair. “I’m so, so sorry.”

She shook her head. “You didn’t do it.”

“I asked you to trust me,” I said. “I told you we would make this work, and I didn’t make it safe enough. That’s my job. We’re going to fix it.”

She didn’t say anything for a long time. Then she said, “Is she leaving?”

“Yes,” I said. “Tonight.”

There are the logistics of an ending. They’re never pretty, and they don’t care about your heart. I got up and called a friend to come over, just to make sure nobody tried to escalate. I told Ella to start packing. I told the girls to gather their things from Stephanie’s room. I kept my voice even. I didn’t want my anger to be another thing Stephanie had to absorb. I walked into the bedroom and lifted the quilt, as gently as if it were a person. I folded it and put it back at the foot of the bed. I took the shirts from the girls and said, “These belong to Stephanie.” They scowled and mumbled but handed them over. I wasn’t here for their understanding. I was here for my daughter.

It took a couple of hours to undo a single day’s harm. We carried boxes back to the door. I asked Ella not to speak to Stephanie. I asked her to speak to me if she needed anything. My friend stood by the doorway, a quiet witness to the end of a chapter. At one point, Ella hissed at me that I was overreacting, that love means adjusting, that I was throwing away a future because of a bedroom. I told her gently but firmly that it wasn’t a bedroom. It was a promise. She didn’t understand. She didn’t need to.

When the last box was out and the door closed behind them, the house got quiet again. It wasn’t the same quiet as before. It was a quiet that knew it had been broken and stitched back up. I went to the basement and knelt on the cold floor and collected Stephanie’s things. I righted the picture frame and wiped the dust off the glass. I carefully set the art cart back onto its wheels. I picked up the little jewelry box and jiggled the lid just right so the song could finish without that strained wobble. Then I carried it all upstairs, one piece at a time, like an act of prayer.

Stephanie stood in the doorway of her room, watching me. “Dad,” she said, “you don’t have to do it all tonight.”

“I want to,” I said. “I want you to sleep in your room, with your things where they belong.”

She nodded and helped me put her clothes back into drawers. We smoothed the quilt. We propped the pillows the way she likes. We set her sketchbooks on the desk. She opened the jewelry box and took out the small silver locket inside, the one with a picture of her mom. She touched the photo with her fingertip and then put the locket back. “Thank you,” she said.

“You don’t have to thank me for doing my job,” I replied. “But I’ll always take a hug.”

She gave me one, tight and clinging. After she let go, she looked around and smiled for the first time that day. It wasn’t a big smile. It was enough.

The next morning, we ate breakfast at the table like usual, bowls and spoons and toast crumbs. The house was still. It felt bigger, but in a way that made sense again. At school drop-off, Stephanie squeezed my hand before she got out. “It’s okay now,” she said, and I said, “It will be,” which felt like the truth.

In the days that followed, people had opinions. They always do. Some thought I moved too fast. Some thought I should have tried to work it out. Some thought I should have expected it. Some were proud of me. None of them were me, and none of them were Stephanie. I didn’t need a committee to vote on the integrity of my home.

Ella called once to say I’d humiliated her. I told her I was sorry she felt humiliated and that I still hoped she and her kids found a stable place where they could be happy. I also told her that if she ever spoke to me again about fairness while stepping on my daughter’s heart, I would hang up. Then I hung up. I blocked her number. I un-wove our plans and returned the ring to the jeweler. Life is a lot of adding and subtracting. People come into your life and teach you something. Sometimes they teach you joy. Sometimes they teach you where your line is.

I keep thinking about that word she used—shrine. I keep rolling it around in my head like a pebble I can’t stand in my shoe. Maybe to some people, a room full of memories looks like worship of the past. To me, it looks like love that’s still doing its work. It looks like a place where a girl can remember her mom while also being a teenager who leaves her socks on the floor and drinks too much fizzy water. It looks like a place where grief is allowed to be quiet and where joy is allowed to be loud. It looks like a place where a dad, even a tired one, can keep a promise.

Not long after, on a Saturday, Stephanie and I went to the farmer’s market. We bought peaches that stained our fingers. We walked through a stall of secondhand books and pretended we had space for more. We talked about school and friends and a math test she didn’t want to take. We didn’t talk about the move or the un-move or the argument. It wasn’t that we were avoiding it. We had said what needed saying. Now we were living.

That afternoon, Stephanie went to her room and shut the door. I heard the muffled sound of music through the wall, her music, the kind with lyrics that repeat the same line until it sounds like a promise. I sat on the couch with a cup of coffee and let the sound fill the house. It felt right, the way a book feels when you’ve put the bookmark back where it belongs. The dog climbed up beside me and rested his chin on my leg. I scratched behind his ears and looked out at the maple tree moving in the breeze.

Being a parent means you will always be a little afraid. You’ll always be scanning the horizon for trouble. But it also means you get to choose, over and over, to stand in front of your child like a wall. Sometimes the world tries to move the wall by calling it selfish or inflexible. Sometimes it tries to convince you that fairness means flattening the person you are meant to protect. Those are the times you dig in your heels. Those are the times you say, my daughter is not the center of the universe, but she is the center of mine.

Ella and I were not cruel to each other because we loved cruelty. We were unfit because our definitions didn’t line up where it mattered most. Maybe somewhere there’s a man who will be the center of her version of fairness. Maybe somewhere there’s a house where two of her girls can bounce on a bed and it will be theirs. I hope they find it. As for me, we already found ours. It’s the sea-green room at the end of the hall with the private bathroom and the closet that smells like lavender. It’s the hallway where a dad walks past and hears the sound of a tinny music box playing a brave, steady tune.

Sometimes at night, after Stephanie’s light clicks off, I stand in the doorway for a minute. I’m not guarding anything, not really. I’m just taking it in, like a captain checking his ship, not because he doubts it floats, but because his heart floats better when he looks. On the dresser is the jewelry box, lid closed, music resting. On the wall are the photos that chart a life. On the desk is a sketch she’s working on—a maple branch with a scatter of leaves, the lines gentle and careful. The quilt is smoothed, the pillows patient. Everything is ordinary, which is the most beautiful thing I know.

I used to think love was mostly sweetness and the right kind of surprises. Now I know love, real love, is mostly choices. It’s the choice to listen when your child says, this hurts. It’s the choice to say no when someone says, but it would be easier my way. It’s the choice to hold onto a promise when letting go would be simpler. It’s the choice to end an engagement in your own kitchen because your daughter’s heart matters more than your pride, your loneliness, your plans.

My name is Johnny. I’m forty-five. I do not have all the answers. I get tired. I mess up and apologize and try again. But I know this: when my daughter needed me to draw a line, I drew it, and I did not let anyone step over it. She is fourteen now, growing in ways that are loud and quiet, obvious and secret. One day she will leave this house and build her own. When she does, I hope she takes with her the certainty that in the hardest moment, I chose her. I hope she remembers the night we put her room back together, piece by piece, and how the house seemed to exhale. I hope she remembers the way the little music box finally found its tune.

And if she ever doubts, if the world ever tries to convince her she deserves less than what love promises, she can open that jewelry box, or run her fingers over the stitches in the quilt, or just close her eyes in any room and hear her dad’s voice, steady and simple: Your home is yours. Your heart is safe here. I’ve got you.